Good: The Fall of Constantinople pdf download

| Excel to pdf free converter download | |

| Version 5.0 lollipop download | |

| Gamecube fire emblem iso download |

Fall of Constantinople

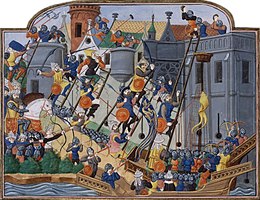

The Fall of Constantinople (Byzantine Greek: Ἅλωσις τῆς Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, romanized: Hálōsis tē̂s Kōnstantinoupóleōs; Turkish: İstanbul'un Fethi, lit. 'Conquest of Istanbul') was the capture of the Byzantine Empire's capital by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453,[5] the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun on 6 April 1453.

The attacking Ottoman army, which significantly outnumbered Constantinople's defenders, was commanded by the 21-year-old SultanMehmed II (later called "the Conqueror"), while the Byzantine army was led by EmperorConstantine XI Palaiologos. After conquering the city, Mehmed II made Constantinople the new Ottoman capital, replacing Adrianople.

The Fall of Constantinople marked the end of the Byzantine Empire, and effectively the end of the Roman Empire, a state which dated back to 27 BC and lasted nearly 1,500 years.[6] The capture of Constantinople, a city which marked the divide between Europe and Asia Minor, also allowed the Ottomans to more effectively invade mainland Europe, eventually leading to Ottoman control of much of the Balkan peninsula.

The conquest of Constantinople and the fall of the Byzantine Empire[7] was a key event of the Late Middle Ages and is sometimes considered the end of the Medieval period.[8] The city's fall also stood as a turning point in military history. Since ancient times, cities and castles had depended upon ramparts and walls to repel invaders. However, Constantinople's substantial fortifications were overcome with the use of gunpowder, specifically in the form of large cannons and bombards.[9]

State of the Byzantine Empire[edit]

Constantinople had been an imperial capital since its consecration in 330 under Roman emperor Constantine the Great. In the following eleven centuries, the city had been besieged many times but was captured only once before: the Sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204.[10]:304 The crusaders established an unstable Latin state in and around Constantinople while the remainder of the Byzantine Empire splintered into a number of successor states, notably Nicaea, Epirus and Trebizond. They fought as allies against the Latin establishments, but also fought among themselves for the Byzantine throne.

The Nicaeans eventually reconquered Constantinople from the Latins in 1261, reestablishing the Byzantine Empire under the Palaiologos dynasty. Thereafter, there was little peace for the much-weakened empire as it fended off successive attacks by the Latins, Serbs, Bulgarians and Ottoman Turks.[10][page needed][11][12][13]

Between 1346 and 1349 the Black Death killed almost half of the inhabitants of Constantinople.[14] The city was further depopulated by the general economic and territorial decline of the empire, and by 1453, it consisted of a series of walled villages separated by vast fields encircled by the fifth-century Theodosian Walls.

By 1450, the empire was exhausted and had shrunk to a few square kilometers outside the city of Constantinople itself, the Princes' Islands in the Sea of Marmara and the Peloponnese with its cultural center at Mystras. The Empire of Trebizond, an independent successor state that formed in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, was also present at the time on the coast of the Black Sea.

Preparations[edit]

When Mehmed II succeeded his father in 1451, he was just nineteen years old. Many European courts assumed that the young Ottoman ruler would not seriously challenge Christian hegemony in the Balkans and the Aegean.[15] This calculation was boosted by Mehmed's friendly overtures to the European envoys at his new court.[10]:373 But Mehmed's mild words were not matched by his actions. By early 1452, work began on the construction of a second fortress (Rumeli hisarı) on the European side of the Bosphorus,[16] several miles north of Constantinople. The new fortress sat directly across the strait from the Anadolu Hisarı fortress, built by Mehmed's great-grandfather Bayezid I. This pair of fortresses ensured complete control of sea traffic on the Bosphorus[10]:373 and defended against attack by the Genoese colonies on the Black Sea coast to the north. In fact, the new fortress was called Boğazkesen, which means "strait-blocker" or "throat-cutter". The wordplay emphasizes its strategic position: in Turkish boğaz means both "strait" and "throat". In October 1452, Mehmed ordered Turakhan Beg to station a large garrison force in the Peloponnese to block Thomas and Demetrios (despotes in Southern Greece) from providing aid to their brother Constantine XI Palaiologos during the impending siege of Constantinople.[note 2]Karaca Pasha, the beylerbeyi of Rumelia, sent men to prepare the roads from Adrianople to Constantinople so that bridges could cope with massive cannon. Fifty carpenters and 200 asistans also strengthened the roads where necessary.[18] The Greek historian Michael Critobulus quotes Mehmed II's speech to his soldiers before the siege:[19]:23

My friends and men of my empire! You all know very well that our forefathers secured this kingdom that we now hold at the cost of many struggles and very great dangers and that, having passed it along in succession from their fathers, from father to son, they handed it down to me. For some of the oldest of you were sharers in many of the exploits carried through by them—those at least of you who are of maturer years—and the younger of you have heard of these deeds from your fathers. They are not such very ancient events nor of such a sort as to be forgotten through the lapse of time. Still, the eyewitness of those who have seen testifies better than does the hearing of deeds that happened but yesterday or the day before.

European support[edit]

Byzantine EmperorConstantine XI swiftly understood Mehmed's true intentions and turned to Western Europe for help; but now the price of centuries of war and enmity between the eastern and western churches had to be paid. Since the mutual excommunications of 1054, the Pope in Rome was committed to establishing authority over the eastern church. The union was agreed by the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos in 1274, at the Second Council of Lyon, and indeed, some Palaiologoi emperors had since been received into the Latin Church. Emperor John VIII Palaiologos had also recently negotiated union with Pope Eugene IV, with the Council of Florence of 1439 proclaiming a Bull of Union. The imperial efforts to impose union were met with strong resistance in Constantinople. A propaganda initiative was stimulated by anti-unionist Orthodox partisans in Constantinople; the population, as well as the laity and leadership of the Byzantine Church, became bitterly divided. Latent ethnic hatred between Greeks and Italians, stemming from the events of the Massacre of the Latins in 1182 by the Greeks and the Sack of Constantinople in 1204 by the Latins, played a significant role. Ultimately, the attempted union between east and west failed, greatly annoying Pope Nicholas V and the hierarchy of the Roman church.

In the summer of 1452, when Rumelı Hisari was completed and the threat of the Ottomans had become imminent, Constantine wrote to the Pope, promising to implement the union, which was declared valid by a half-hearted imperial court on 12 December 1452.[10]:373 Although he was eager for an advantage, Pope Nicholas V did not have the influence the Byzantines thought he had over the Western kings and princes, some of whom were wary of increasing papal control. Furthermore, these Western rulers did not have the wherewithal to contribute to the effort, especially in light of the weakened state of France and England from the Hundred Years' War, Spain's involvement in the Reconquista, the internecine fighting in the Holy Roman Empire, and Hungary and Poland's defeat at the Battle of Varna of 1444. Although some troops did arrive from the mercantile city-states in northern Italy, the Western contribution was not adequate to counterbalance Ottoman strength. Some Western individuals, however, came to help defend the city on their own account. Cardinal Isidore, funded by the Pope, arrived in 1452 with 200 archers.[20] An accomplished soldier from Genoa, Giovanni Giustiniani, arrived in January 1453 with 400 men from Genoa and 300 men from Genoese Chios.[21]:83–84 As a specialist in defending walled cities, Giustiniani was immediately given the overall command of the defence of the land walls by the Emperor. Around the same time, the captains of the Venetian ships that happened to be present in the Golden Horn offered their services to the Emperor, barring contrary orders from Venice, and Pope Nicholas undertook to send three ships laden with provisions, which set sail near the end of March.[21]:81

Meanwhile, in Venice, deliberations were taking place concerning the kind of assistance the Republic would lend to Constantinople. The Senate decided upon sending a fleet in February 1453, but the fleet's departure was delayed until April, when it was already too late for ships to assist in battle.[22][page needed][21]:85 Further undermining Byzantine morale, seven Italian ships with around 700 men, despite having sworn to defend Constantinople, slipped out of the capital the moment when Giustiniani arrived. At the same time, Constantine's attempts to appease the Sultan with gifts ended with the execution of the Emperor's ambassadors.[10]:373[23][24][25][26][27][28]

Fearing a possible naval attack along the shores of the Golden Horn, Emperor Constantine XI ordered that a defensive chain be placed at the mouth of the harbour. This chain, which floated on logs, was strong enough to prevent any Turkish ship from entering the harbour. This device was one of two that gave the Byzantines some hope of extending the siege until the possible arrival of foreign help.[22]:380 This strategy was enforced because in 1204, the armies of the Fourth Crusade successfully circumvented Constantinople's land defences by breaching the Golden Horn Wall. Another strategy employed by the Byzantines was the repair and fortification of the Land Wall (Theodosian Walls). Emperor Constantine deemed it necessary to ensure that the Blachernae district's wall was the most fortified because that section of the wall protruded northwards. The land fortifications consisted of a 60 ft (18 m) wide moat fronting inner and outer crenellated walls studded with towers every 45–55 metres.[29]

Strength[edit]

The army defending Constantinople was relatively small, totalling about 7,000 men, 2,000 of whom were foreigners.[note 3] At the onset of the siege, probably fewer than 50,000 people were living within the walls, including the refugees from the surrounding area.[30]:32[note 4] Turkish commander Dorgano, who was in Constantinople working for the Emperor, was also guarding one of the quarters of the city on the seaward side with the Turks in his pay. These Turks kept loyal to the Emperor and perished in the ensuing battle. The defending army's Genoese corps were well trained and equipped, while the rest of the army consisted of small numbers of well-trained soldiers, armed civilians, sailors and volunteer forces from foreign communities, and finally monks. The garrison used a few small-calibre artillery pieces, which in the end proved ineffective. The rest of the citizens repaired walls, stood guard on observation posts, collected and distributed food provisions, and collected gold and silver objects from churches to melt down into coins to pay the foreign soldiers.

The Ottomans had a much larger force. Recent studies and Ottoman archival data state that there were some 50,000–80,000 Ottoman soldiers, including between 5,000 and 10,000 Janissaries,[31][page needed], 70 cannons[32]:139–140[30][page needed][33][page needed], an elite infantry corps. Contemporaneous Western witnesses of the siege, who tend to exaggerate the military power of the Sultan, provide disparate and higher numbers ranging from 160,000 to 300,000[31][page needed](Niccolò Barbaro:[34] 160,000; the Florentine merchant Jacopo Tedaldi[35] and the Great Logothete George Sphrantzes:[36][page needed] 200,000; the Cardinal Isidore of Kiev[37] and the Archbishop of Mytilene Leonardo di Chio:[38] 300,000).[39]

Ottoman dispositions and strategies[edit]

Mehmed built a fleet (partially manned by Spanish sailors from Gallipoli) to besiege the city from the sea.[30][page needed] Contemporary estimates of the strength of the Ottoman fleet span from 110 ships to 430. (Tedaldi:[35] 110; Barbaro:[34] 145; Ubertino Pusculo:[40] 160, Isidore of Kiev[37] and Leonardo di Chio:[41] 200–250; (Sphrantzes):[36][page needed] 430) A more realistic modern estimate predicts a fleet strength of 110 ships comprising 70 large galleys, 5 ordinary galleys, 10 smaller galleys, 25 large rowing boats, and 75 horse-transports.[30]:44

Before the siege of Constantinople, it was known that the Ottomans had the ability to cast medium-sized cannons, but the range of some pieces they were able to field far surpassed the defenders' expectations.[10]:374 The Ottomans deployed a number of cannons, anywhere from 50 cannons to 200. They were built at foundries that employed Turkish cannon founders and technicians, most notably Saruca, in addition to at least one foreign cannon founder, Orban (also called Urban). Most of the cannons at the siege were built by Turkish engineers, including a large bombard by Saruca, while one cannon was built by Orban, who also contributed a large bombard.[42][43]

Orban, a Hungarian (though some suggest he was German), was a somewhat mysterious figure.[10]:374 His 27 feet (8.2 m) long cannon was named "Basilica" and was able to hurl a 600 lb (270 kg) stone ball over a mile (1.6 km).[44] Orban initially tried to sell his services to the Byzantines, but they were unable to secure the funds needed to hire him. Orban then left Constantinople and approached Mehmed II, claiming that his weapon could blast "the walls of Babylon itself". Given abundant funds and materials, the Hungarian engineer built the gun within three months at Edirne.[21]:77–78 However, this was the only cannon that Orban built for the Ottoman forces at Constantinople,[42][43] and it had several drawbacks: it took three hours to reload; cannonballs were in very short supply; and the cannon is said to have collapsed under its own recoil after six weeks. The account of the cannon's collapse is disputed,[31][page needed] given that it was only reported in the letter of Archbishop Leonardo di Chio[38] and in the later, and often unreliable, Russian chronicle of Nestor Iskander.[note 5]

Having previously established a large foundry about 150 miles (240 km) away, Mehmed now had to undertake the painstaking process of transporting his massive artillery pieces. In preparation for the final assault, Mehmed had an artillery train of 70 large pieces dragged from his headquarters at Edirne, in addition to the bombards cast on the spot.[45] This train included Orban's enormous cannon, which was said to have been dragged from Edrine by a crew of 60 oxen and over 400 men.[10]:374[21]:77–78 There was another large bombard, independently built by Turkish engineer Saruca, that was also used in the battle.[42][43]

Mehmed planned to attack the Theodosian Walls, the intricate series of walls and ditches protecting Constantinople from an attack from the West and the only part of the city not surrounded by water. His army encamped outside the city on 2 April 1453, the Monday after Easter.

The bulk of the Ottoman army was encamped south of the Golden Horn. The regular European troops, stretched out along the entire length of the walls, were commanded by Karadja Pasha. The regular troops from Anatolia under Ishak Pasha were stationed south of the Lycus down to the Sea of Marmara. Mehmed himself erected his red-and-gold tent near the Mesoteichion, where the guns and the elite Janissary regiments were positioned. The Bashi-bazouks were spread out behind the front lines. Other troops under Zagan Pasha were employed north of the Golden Horn. Communication was maintained by a road that had been destroyed over the marshy head of the Horn.[21]:94–95

Byzantine dispositions and strategies[edit]

The city had about 20 km of walls (land walls: 5.5 km; sea walls along the Golden Horn: 7 km; sea walls along the Sea of Marmara: 7.5 km), one of the strongest sets of fortified walls in existence. The walls had recently been repaired (under John VIII) and were in fairly good shape, giving the defenders sufficient reason to believe that they could hold out until help from the West arrived.[30]:39 In addition, the defenders were relatively well-equipped with a fleet of 26 ships: 5 from Genoa, 5 from Venice, 3 from Venetian Crete, 1 from Ancona, 1 from Aragon, 1 from France, and about 10 from the empire itself.[30]:45

On 5 April, the Sultan himself arrived with his last troops, and the defenders took up their positions. As Byzantine numbers were insufficient to occupy the walls in their entirety, it had been decided that only the outer walls would be manned. Constantine and his Greek troops guarded the Mesoteichion, the middle section of the land walls, where they were crossed by the river Lycus. This section was considered the weakest spot in the walls and an attack was feared here most. Giustiniani was stationed to the north of the emperor, at the Charisian Gate (Myriandrion); later during the siege, he was shifted to the Mesoteichion to join Constantine, leaving the Myriandrion to the charge of the Bocchiardi brothers. Minotto and his Venetians were stationed in the Blachernae Palace, together with Teodoro Caristo, the Langasco brothers, and Archbishop Leonardo of Chios.[21]:92

To the left of the emperor, further south, were the commanders Cataneo, who led Genoese troops, and Theophilus Palaeologus, who guarded the Pegae Gate with Greek soldiers. The section of the land walls from the Pegae Gate to the Golden Gate (itself guarded by a Genoese called Manuel) was defended by the Venetian Filippo Contarini, while Demetrius Cantacuzenus had taken position on the southernmost part of the Theodosian wall.[21]:92

The sea walls were manned more sparsely, with Jacobo Contarini at Stoudion, a makeshift defence force of Greek monks to his left hand, and Prince Orhan at the Harbour of Eleutherios. Pere Julià was stationed at the Great Palace with Genoese and Catalan troops; Cardinal Isidore of Kiev guarded the tip of the peninsula near the boom. Finally, the sea walls at the southern shore of the Golden Horn were defended by Venetian and Genoese sailors under Gabriele Trevisano.[21]:93

Two tactical reserves were kept behind in the city: one in the Petra district just behind the land walls and one near the Church of the Holy Apostles, under the command of Loukas Notaras and Nicephorus Palaeologus, respectively. The Venetian Alviso Diedo commanded the ships in the harbour.[21]:94

Although the Byzantines also had cannons, the weapons were much smaller than those of the Ottomans, and the recoil tended to damage their own walls.[38]

According to David Nicolle, despite many odds, the idea that Constantinople was inevitably doomed is incorrect, and the overall situation was not as one-sided as a simple glance at a map might suggest.[30]:40 It has also been claimed that Constantinople was "the best-defended city in Europe" at that time.[46]

Siege[edit]

At the beginning of the siege, Mehmed sent out some of his best troops to reduce the remaining Byzantine strongholds outside the city of Constantinople. The fortress of Therapia on the Bosphorus and a smaller castle at the village of Studius near the Sea of Marmara were taken within a few days. The Princes' Islands in the Sea of Marmara were taken by Admiral Baltoghlu's fleet.[21]:96–97 Mehmed's massive cannon fired on the walls for weeks, but due to its imprecision and extremely slow rate of reloading, the Byzantines were able to repair most of the damage after each shot, mitigating the cannon's effect.[10]:376

Meanwhile, despite some probing attacks, the Ottoman fleet under Baltoghlu could not enter the Golden Horn due to the chain the Byzantines had previously stretched across the entrance. Although one of the fleet's main tasks was to prevent any foreign ships from entering the Golden Horn, on 20 April, a small flotilla of four Christian ships[note 6] managed to slip in after some heavy fighting, an event which strengthened the morale of the defenders and caused embarrassment to the Sultan.[10]:376 Baltoghlu's life was spared after his subordinates testified to his bravery during the conflict.

Mehmed ordered the construction of a road of greased logs across Galata on the north side of the Golden Horn, and dragged his ships over the hill, directly into the Golden Horn on 22 April, bypassing the chain barrier.[10]:376 This action seriously threatened the flow of supplies from Genoese ships from the nominally neutral colony of Pera, and it demoralized the Byzantine defenders. On the night of 28 April, an attempt was made to destroy the Ottoman ships already in the Golden Horn using fire ships, but the Ottomans forced the Christians to retreat with heavy losses. 40 Italians escaped their sinking ships and swam to the northern shore. On orders of Mehmed, they were impaled on stakes, in sight of the city's defenders on the sea walls across the Golden Horn. In retaliation, the defenders brought their Ottoman prisoners, 260 in all, to the walls, where they were executed, one by one, before the eyes of the Ottomans.[21]:108[47] With the failure of their attack on the Ottoman vessels, the defenders were forced to disperse part of their forces to defend the sea walls along the Golden Horn.

The Ottoman army had made several frontal assaults on the land wall of Constantinople, but they were always repelled with heavy losses.[48] Venetian surgeon Niccolò Barbaro, describing in his diary one such land attack by the Janissaries, wrote:

They found the Turks coming right up under the walls and seeking battle, particularly the Janissaries ... and when one or two of them were killed, at once more Turks came and took away the dead ones ... without caring how near they came to the city walls. Our men shot at them with guns and crossbows, aiming at the Turk who was carrying away his dead countryman, and both of them would fall to the ground dead, and then there came other Turks and took them away, none fearing death, but being willing to let ten of themselves be killed rather than suffer the shame of leaving a single Turkish corpse by the walls.[34]

After these inconclusive frontal offensives, the Ottomans sought to break through the walls by constructing tunnels in an effort to mine them from mid-May to 25 May. Many of the sappers were miners of Serbian origin sent from Novo Brdo[50] and were under the command of Zagan Pasha. However, an engineer named Johannes Grant, a German[note 7] who came with the Genoese contingent, had counter-mines dug, allowing Byzantine troops to enter the mines and kill the workers. The Byzantines intercepted the first tunnel on the night of 16 May. Subsequent tunnels were interrupted on 21, 23, and 25 May, and destroyed with Greek fire and vigorous combat. On 23 May, the Byzantines captured and tortured two Turkish officers, who revealed the location of all the Turkish tunnels, which were subsequently destroyed.[51]

On 21 May, Mehmed sent an ambassador to Constantinople and offered to lift the siege if they gave him the city. He promised he would allow the Emperor and any other inhabitants to leave with their possessions. Moreover, he would recognize the Emperor as governor of the Peloponnese. Lastly, he guaranteed the safety of the population that might choose to remain in the city. Constantine XI only agreed to pay higher tributes to the sultan and recognized the status of all the conquered castles and lands in the hands of the Turks as Ottoman possession. However, the Emperor was not willing to leave the city without a fight:

As to surrendering the city to you, it is not for me to decide or for anyone else of its citizens; for all of us have reached the mutual decision to die of our own free will, without any regard for our lives.[note 8]

Around this time, Mehmed had a final council with his senior officers. Here he encountered some resistance; one of his Viziers, the veteran Halil Pasha, who had always disapproved of Mehmed's plans to conquer the city, now admonished him to abandon the siege in the face of recent adversity. Zagan Pasha argued against Halil Pasha and insisted on an immediate attack. Believing that the beleaguered Byzantine defence was already weakened sufficiently, Mehmed planned to overpower the walls by sheer force and started preparations for a final all-out offensive.

Final assault[edit]

Preparations for the final assault began in the evening of 26 May and continued to the next day.[10]:378 For 36 hours after the war council decided to attack, the Ottomans extensively mobilized their manpower in order to prepare for the general offensive.[10]:378 Prayer and resting was then granted to the soldiers on the 28th before the final assault would be launched. On the Byzantine side, a small Venetian fleet of 12 ships, after having searched the Aegean, reached the Capital on 27 May and reported to the Emperor that no large Venetian relief fleet was on its way.[10]:377 On 28 May, as the Ottoman army prepared for the final assault, large-scale religious processions were held in the city. In the evening, a solemn last ceremony was held in the Hagia Sophia, in which the Emperor with representatives and nobility of both the Latin and Greek churches partook.[53]:651–652

Shortly after midnight on 29 May, the all-out offensive began. The Christian troops of the Ottoman Empire attacked first, followed by successive waves of the irregular azaps, who were poorly trained and equipped, and Anatolian Turkmen beylik forces who focused on a section of the damaged Blachernae walls in the north-west part of the city. This section of the walls had been built earlier, in the eleventh century, and was much weaker. The Turkmen mercenaries managed to breach this section of walls and entered the city, but they were just as quickly pushed back by the defenders. Finally, the last wave consisting of elite Janissaries, attacked the city walls. The Genoese general in charge of the land troops,[31][page needed][37][38]Giovanni Giustiniani, was grievously wounded during the attack, and his evacuation from the ramparts caused a panic in the ranks of the defenders.[note 9]

With Giustiniani's Genoese troops retreating into the city and towards the harbour, Constantine and his men, now left to their own devices, continued to hold their ground against the Janissaries. However, Constantine's men eventually could not prevent the Ottomans from entering the city, and the defenders were overwhelmed at several points along the wall. When Turkish flags were seen flying above the Kerkoporta, a small postern gate that was left open, panic ensued, and the defence collapsed. Meanwhile, Janissary soldiers, led by Ulubatlı Hasan, pressed forward. Many Greek soldiers ran back home to protect their families, the Venetians retreated to their ships, and a few of the Genoese escaped to Galata. The rest surrendered or committed suicide by jumping off the city walls.[22][page needed]

0 thoughts to “The Fall of Constantinople pdf download”